A novelist and actor discuss art, perception and lingering stereotypes By Suki Kim NEWSWEEK WEB EXCLUSIVE

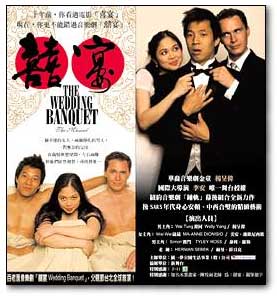

IN 1997, he founded the theater company Second Generation and conceived and co-wrote the company’s first musical, “Making Tracks,” about six generations of an Asian family, which recently completed a two-month run in Seattle. The 30-year-old Yang will be starring in his own musical adaptation of Ang Lee’s film “The Wedding Banquet,” which will have its world premiere in Taiwan on Aug. 8 before coming to the United States. Last week, I met the native New Yorker in Chinatown, just blocks from his theater company, where we talked about the Asian face, the cultural ghetto and J. Lo. Suki Kim: You just got back from Taipei yesterday, where you are producing and starring in a musical version of “The Wedding Banquet.” Why are you doing it? Welly Yang: I have always been interested in works that have social importance. “The Wedding Banquet” was one of the most successful independent films. Actually in that year, it was more profitable than “Jurassic Park.” It’s about the conflict between East and West, between two generations, and the hero who is caught between two worlds and has to negotiate his American life against the weight of traditions. We’ve seen stories about our cultures and society from the Western point of view, and for me it was about bringing a new point of view, a new window in seeing the way our world is in our eyes. And it’s been interesting to translate the film into a musical. So it was a personal decision to premiere it in Taiwan? I wanted it to be in Taiwan first. The story is about a Taiwanese-American in New York. Ang Lee is Taiwanese. Although I was born in this country, my parents are from Taiwan. Taiwan has always been the underdog in the world. They were occupied by Portuguese, Japanese, Dutch. China won’t let them become a member of the United Nations. There are missile threats every other day. I guess I wanted to raise Taiwan’s status. Something in my American side makes me root for the underdog. How was the film “Wedding Banquet” received in Taiwan? It was a success, although the gay theme is still subversive. I think that the Taiwanese society is much more conservative than their government in terms of homosexuality. But things are changing fast in Taiwan because of the economic democratic reforms in the last 10 years. Media has gone crazy there. They follow politicians and TV stars everywhere. There is no privacy almost. You think of New York being a fast city, but we are like France compared to Asia. It’s true. There’s a bit of paranoia and panic you feel in Asia. I go to Seoul, South Korea, about once a year. And it’s like a city on speed. I feel like a country girl when I am there, and I live in the heart of Manhattan! Were you born in Korea? I am what you call the 1.5 generation. I came here when I was 13. English is my second language. I didn’t have the Asian-American experience of growing up here. In Korea, you don’t think of yourself as Asian, which is a relative term. You don’t think about white and black people; you never see them except in movies. This label of Asian-American is something I came here and learned. I learned writing before I learned about being Asian-American. Despite the fact that my novel deals with the Korean-American experience, I still did not think of that as “Asian-American.” It’s something that is being constantly thrown at me, which I am learning to acknowledge, or take advantage of, or just deal with. You are Asian-American and so am I, supposedly. But we have completely different experiences. I know nothing about Taiwan, and that’s not even where you were born. How comfortable are you with the Asian-American artist label? Isn’t it tiring to be perceived as the voice of your people when what you really want is to sit down and make art? The Asian-American movement was defined by the Asian-Americans themselves. It’s a device to give us a voice. For so long, I fought hard to be just like everyone else, to be the same. When I started to perform, I realized I wasn’t the same because of the roles I was getting as an actor. So I began to write and produce, as well. At first, I was not even sure if my company, Second Generation, should be Asian. I thought it should just be a theater company. Then I started thinking about things that were important to me, and everything always came back to telling stories about these experiences. I believe in honesty in art. I am an Asian-American artist because of the work I create and find important to create. I am actively promoting Asian-American stories. As an Asian-American, I am always being typecast anyway, so I have to make that into my strength. The biggest problem with things that are labeled as Asian-American, which can cover anything, is that they are marginal. But then you take a movie like “The Wedding Banquet,” and you really dissect it, and nothing about it is marginal, because it’s a familiar territory. It’s comedy of errors but in a very mainstream, recognizable way. Like the hit movie, “My Big Fat Greek Wedding,” which was really a sitcom with exoticism thrown in it. To bring a marginal story and appeal it to the mainstream audience—how do you do that? I always try to create universal art. The answer lies in the specificity of that story. The more specific I am, the more universal it becomes. Because we all put ourselves in those people whom we identify with. When I first saw the film, “The Wedding Banquet,” I was still in college and was about to decide what I wanted to do with my life. I had spent every summer doing theater and knew that it was my passion. Now I had to face my parents and tell them. Wai Tung coming out in the film was very similar to my own coming out as an artist. For most Asian-American parents, art is not necessarily the path they envision for their children. I don’t know if that’s such an Asian dilemma. I have not had the similar experience personally. My parents have always been encouraging. In a way, I think that is an immigrant dilemma. Fresh immigrants don’t cross the ocean to have your kids turn out to be a singer. That reminds me of a quote by President John Adams, who said that “I study war and politics so my children can study economics, so their children can one day study literature and art.” When I first told my mother I wanted to be an actor, she said, what are you going to do, play a houseboy for the rest of your life? I had just finished playing Ito in the musical “Mame,” and my lines were all like “Speak no English, Auntie Mame.” Why are there so few Asians in theater and film? Asians were only properly allowed in this country since 1965 [before which there were quotas on Asian immigrants]. We’ve been here, but not in numbers that make a significant impact. People tell stories of what they know. There aren’t a lot of Asian people doing that. People are writing from the Jewish experience or WASP experience. When later generations study who we were, they will look at our culture—literature, theater, art. When Asians are absent from that, it’s wrong. I think it’s a human-rights issue. It’s like saying, there are only certain things available to you in this world, and these things are not because you look like this. I admire Ang Lee who can turn around and make “Sense and Sensibility” and “Ice Storm,” as well as “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,” “The Wedding Banquet” and now “The Hulk.” The choices he’s made have been brilliant. It’s about not being pigeon-holed. How do you personally transcend having to play only a houseboy or a kung-fu master? There are jazz purists who dictate what is and what isn’t. If it’s borrowing from that tradition, isn’t the reinterpretation of jazz reflecting what our society is today, and in some way, more important than the museum type of jazz? Museum is what segregates and pushes away. It’s not fluid, but frozen in time. We have to keep redefining what Asian-American is. I don’t want to be ghettoized. But at the same time, I do want to embrace the diverse Asian-American voices. You need both to be able create a movement. You need the wacky guy and the conservative, so people can accept you. You need Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. It’s about opening new doors, new possibilities. So a kid in Chinatown can say I want to be on Broadway. That can be in his world of possibility, because right now it isn’t. So you are turning your own Asian-Americaness into your strength, like being Hispanic is suddenly trendy with the emergence of Jennifer Lopez. As much as I don’t like labels, I don’t think that’s something I can control. Jennifer Lopez—next time Joe Shmuck from Idaho meets a person of Hispanic heritage, she won’t be so foreign anymore, because he knows J. Lo. So it’s the same with Asian-Americans. I love being able to say I am Taiwanese. So when a Taiwanese kid plays in a playground, he won’t be mocked by another ignorant kid calling him a chink because that ignorant kid will now know that he’s seen someone who looks like that. It’s deeply moving to me. I had a cable talk show here in New York. When I was little, I never saw Asian people on TV. I think it’s important to see people who look like you in the world. When we see those leads who are of different race than what we are used to, it begins to break down our perception of what is and what isn’t. It’s about knowing those people. When you stay an hour or two with people who are different from you, you can’t help but discover their humanity and see that they are 99.9 percent the same as you—the same pain, hatred, love. Personally, as a writer, when I get reviews like “if you like ‘Joy Luck Club,’ you will like Suki Kim’s ‘The Interpreter’,” I feel uncomfortable. Suddenly, because of my skin color, I am compared to every other Asian-American writer, despite the vast difference in our writing styles. You need to give people in the world a door. If that door is “Joy Luck Club,” and they buy your book, is that bad? I understand that it’s a marketing decision. But as a writer, you love language, everything is about language, then you face that reviewers cannot seem to get over your skin color or your heroine’s skin color. Suddenly, my Asian-Americaness starts to overwhelm my writing. I have never felt more Asian-American as I have since my novel came out. Perhaps I am more easily offended and surprised because I am newer at being American than you are. As an actor, I face the same frustration all the time. Once, I showed up at an audition for an all-American role, and they said, oh, you are not exactly what we are looking for, and I said, what do you mean?, I went to Lawrenceville boarding school [in New Jersey] and Columbia University, why am I not all-American? Then later, in “Miss Saigon,” I played the role of the evil Vietcong Thuy, but I had actually auditioned for Chris, the white lead. I am a tenor; I can sing that stuff easily. I said to them that I realized that he had to be white because of the racist, imperialist, misogynistic nature of the story, but that I had found the way around it. I had found a makeup artist who could build me eye sockets and a nose or whatever. And they said, no. They had the familiar excuse, but mainly there was that “Asian Face” problem. The historical context is that Asian people have never played white people, and for centuries, white people have played Asian people. All of a sudden, when an Asian person says he wants to play the white person, everyone says, you’re crazy. They thought I lost my marbles. Have I really? Or is the racist reality of our society that makes it seem like I am crazy? You can’t look at things in vacuum, because they ultimately always exist in a political context. That reminds me of the novel, “Memoirs of a Geisha.” I had no problem with a white American man writing in the voice of a geisha. But what bothered me was the absurd content—that the celebrated geisha has blue eyes and begins to admire her American clients for their directness and eventually moves to New York, all despite the American bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. First of all, a blue-eyed geisha would have been considered a freak, not a beauty. The story was told with no irony at all. I found it offensive and considered it a gross example of the Americanization of the Asian culture. Even in the world of fiction, language is historical and has a sociopolitical memory. You can do anything you want, but you have to be responsible once you decide to take on the task. You never enter an innocent territory. Is the topic of your next work non-Asian? Let’s just say it’s not a Korean-American story. It’s not the decision to go against your people. I have already written “The Interpreter.” I am moving on to a new subject. Do you think you will get it published then? That would be assuming that the only reason that “The Interpreter” was published was because its author was Asian and the story was Asian. I hope that was not the case. Hopefully, I could even write a book about a Southern belle and be accepted the same. If Ang Lee could do “The Hulk,” why couldn’t I write whatever inspires me? As you said before, it is the specificity of the story that reaches universality. Maybe you are like Ang Lee and I am like Spike Lee. The difference between Spike Lee and Ang Lee is that Spike said, these are the things that are important, I am gonna do Malcolm X, get on a bus and stay there, but Ang Lee will do whatever he wants do at that given moment. Although my work might be more like Spike Lee, I do want to produce them like Ang Lee. I see the freedom and the excitement of being Ang Lee as an actor. I see the value of supporting actors who want to be Ang Lee. Once you have the audience who are not in your cultural ghetto, you are preaching to those beyond the converted. Then you have the power to expand. It’s always about expanding, including the definition of Asian-American. Everyone could be Asian-American. J. Lo could be Asian-American. Spike Lee also. The more people, the better. Boundaries should be broken. Suki Kim’s first novel, “The Interpreter,” was published earlier this year by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. http://www.msnbc.com/news/937361.asp |